Last week I attended IFA in Berlin, perhaps Europe’s biggest consumer electronics event, and was struck by the ubiquity of Google Assistant. The company spent big on promoting its digital assistant both outside and inside the venue.

Mach mal, Google; or in English, Go Google.

On the stands and in press briefings I soon lost count of who was supporting Google’s voice assistant. A few examples:

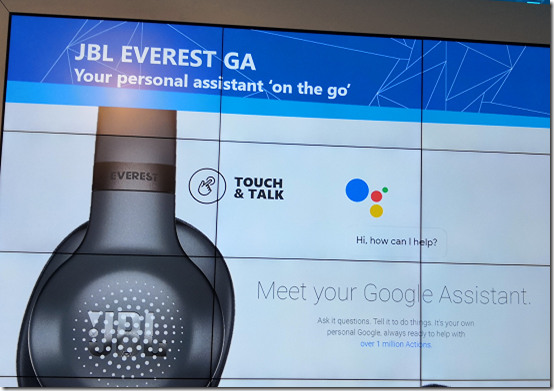

JBL/Harman in its earbuds

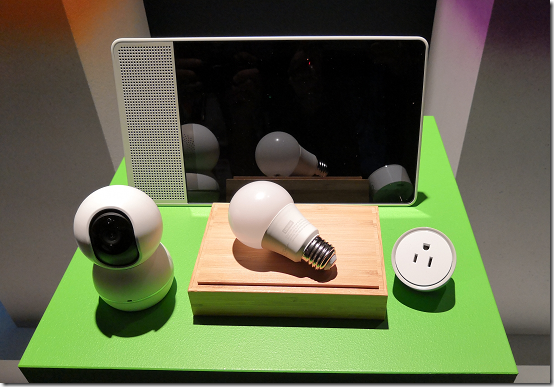

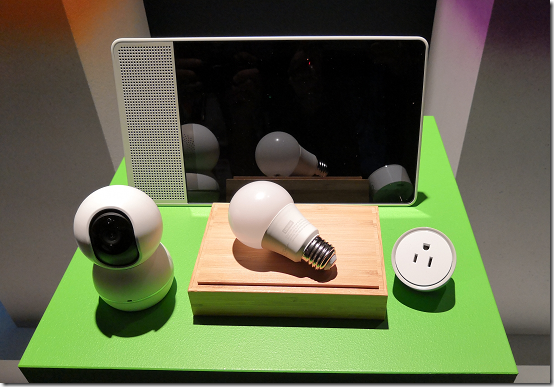

Lenovo with its Home Control Solutions – Lenovo also uses its own cloud and will support Amazon Alexa

LG with audio, TV, kitchen, home automation and more

Bang & Olufsen with its smart speakers. No logo, but it is using Google Assistant both as a feature in itself (voice search and so on) and to control other audio devices.

And Sony with its TVs and more. For example, then new AF9 and ZF9 series: “Using the Google Assistant with both the AF9 and ZF9 will be even easier. Both models have built-in microphones that will free the hands; now you simply talk to the TV to find what you quickly want, or to ask the Google Assistant to play TV shows, movies, and more.*

I was only at IFA for the pre-conference press days so this is just a snapshot of what I saw; there were many more Google Assistant integrations on display, and quite a few (though not as many) for Amazon Alexa.

It is fair to say then that Google is treating this as a high priority and having considerable success in getting vendors to sign up.

What is Google Assistant?

Google Assistant really only needs three things in order to work. A microphone, to hear you. An internet connection, to send your voice input to its internet service for voice to text transcription, and then to its AI/Search service to find a suitable response. And a speaker, to output the result. You can get it as a product called Google Home but it is the software and internet service that counts.

Vendors of smart devices – anything that has an internet connection – can develop integrations so that Google Assistant can control them. So you can say, “Hey Google, turn on the living room light” and it will be so. Cool.

Amazon Alexa has similar features and this is Google’s main competition. Alexa was first and ties in well with Amazon services such as shopping and media. However Google has the advantage of its search services, its control of Android, and its extensive personal data derived from search, Android, Google Maps and location services, GMail and more. This means Google can do better AI and richer personalisation.

Natural language UI

Back in March I attended an AI Assistant Summit in London organised by Re-Work. One of the speakers was Yariv Adan, a Product Lead at Google Assistant.

I attend lots of presentations but this one made a particular impact on me. Adan believes that natural language UI is the next big technological shift. The preceding ones he identified were the Internet in the nineties and smartphones in the early years of this century. Adan envisages an era in which we no longer constantly pull out devices.

“I believe the next revolution is happening now, powered by AI. I call it the paradigm switch to natural UI. Instead of humans adapting to machines, machines adapt to humans. What we’re trying to create is we interact with machines the same way we interact with each other, in a natural way. Meaning using natural language, showing things, pointing at things, assuming context, assuming a human-like memory, expecting personality, humour, opinion, some kind of an emotional connection, empathy.

[In future] it is not the device changing, it is the device disappearing. We are not going to interact with devices any more. We are starting to interact with this AI entity, an ambient entity that exists everywhere.”

Note: If you ever read Isaac Asimov’s science fiction novels, you will recognise this as very like his Multivac computer, which hears and responds to your questions wherever you are.

“Imagine now that everything is connected, that the entity follows you. That there is no more device that you need to take out, turn on, speak to it. It’s around you, it’s on the TV, it’s in the speakers, it’s in your headphones, it’s in the watch, it’s in the auto, it’s there. Internet of things, any connected device that only has a speaker you can actually start interacting with that thing,”

said Adan.

Adan gave a number of demonstrations. Incidentally, he never uttered the words “Hey Google”. Simply, he spoke into his phone, where I presume some special version of Google Assistant was running. In particular, he was keen to show how the AI is learning about context and memory. So he asked what is the largest castle in the UK where people live. Answer: Windsor Castle. Then, Who built it? When? Is it open now? How can I get there by public transport? What about food? In each case, the Assistant answered as a human would, understanding that the topic was Windsor Castle. “I found some restaurants within 0.4 miles,” said the Assistant, betraying a touch of computer-style logic.

“Thank you you’re awesome,” says Adan. “Not a problem”, responds the Assistant. This is an example of personality or emotion, key factors, said Adan, in making interaction natural.

Adan also talked about personalisation. “Show me my flight”. The Assistant knows he is away from home and also has access to his mailbox, from where it has parse flight details. So it answers this generic question with specific details about tomorrow’s flight to Zurich.

“Where did I park my car?” In this case, Adan had taken a picture of his car after parking. The Assistant knew the location of the picture and was able to show both the image and its place on a map.

“I want to show how we use some of that power for the ecosystem that we have built … we’re trying to make that revolution to a place where you don’t need to think about the machine any more, where you just interact in a way that is natural. I am optimistic, I think the revolution is happening now.”

Implications and unintended consequences

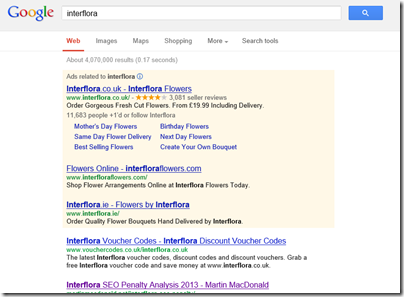

An earlier speaker at the Re-Work event (sorry I forget who it was) noted that voice systems give simplified results compared to text-based searches. Often you only get one result. Back in the nineties, we used to talk about “10 blue links” as the typical result of a search. This meant that you had some sort of choice about where you clicked, and an easy way to get several different perspectives. Getting just one result is great if the answer is purely factual and is correct, but reinforces the winner-takes-all tendency. Instead of being on the first page of results, you have to be top. Or possibly pay for advertising; that aspect has not yet emerged in the voice assistant world.

If we get into the habit of shopping via voice assistants, it will be disruptive for brands. Maybe Amazon Basics will do well, if users simply say “get me some A4 paper” rather than specifying a brand. Maybe more and more decisions will be taken for you. “Get me a takeaway dinner”, perhaps, with the assistant knowing both what you like, and what you ate yesterday and the day before.

All this is speculation, but it is obvious that a shift from screens to voice for both transactions and information will have consequences for vendors and information providers; and that probably it will tend to reduce rather than increase diversity.

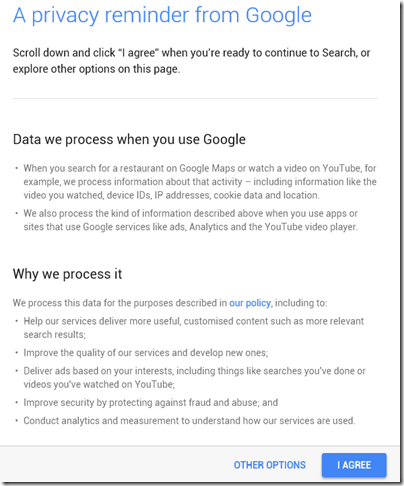

What about your personal data? This is a big question and one that the industry hates to talk about. I heard nothing about it at IFA. The assumption was that if you could turn on a light, or play some music, without leaving your chair, that must be a good thing. Yet, having a device or devices in your home listening to your every word (in case you might say “Hey Google”) is something that makes me uncomfortable. I do not want Google reading my emails or tracking my location, but it is becoming hard to avoid.

For most people, Google Assistant will just be a feature of their TV, or audio system, or a way to call up recipes in the kitchen.

From Google’s perspective though, it is safe to assume that the ability to collect data is a key reason for its strong promotion and drive behind Google Assistant. That data has enormous value. Targeted advertising is the start, but it also provides deep insight into how we live, trends in human behaviour, changing patterns of consumption, and much more. When things are going wrong with our health, our finances or our relationships, it is not implausible that Google may know before we do.

This is a lot of power to give a giant US corporation; and we should also note that in some scenarios, if the US government were to demand that data be handed over, a company like Google has no choice but to comply.

Personalisation can make our lives better, but also has the potential to harm us. An area of concern is that of shared risk, such as health insurance. Insurers may be reluctant to give policies to those people most likely to make a claim. Could Google’s data store somehow end up impacting our ability to insure, or its cost?

Personalisation is always a trade-off. Organisation gets my data; I get a benefit. I shop at a supermarket and this is fairly transparent. I use a loyalty card so the shop knows what I buy; in return I get discount points and special offers.

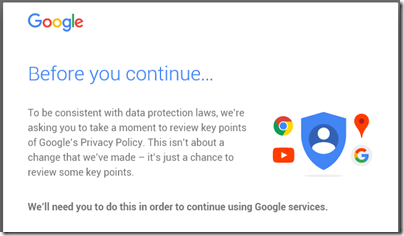

In the case of Google Assistant it is not so transparent. The EU’s GDPR legislation has helped, giving citizens the right to access their data and the right to be forgotten. However, we are still in the era of one-sided privacy policies and in many cases the binary choice of agree, or do not use our services. This becomes a problem if the service provider has anything close to a monopoly, which is true in Google’s case. Regulation, it seems to me, is exactly the right answer to the risks inherent in putting too much power in the hands of a business entity.

For myself, I am happy to cross the room and turn on the light, and to find my flight in my calendar. The trade-off is not worth it. But if Adan’s “ambient entity” comes to pass (which is actually most likely Google) I am not sure of the extent to which I will have a choice.

Adan’s work is terrific and the ability for machines to converse with humans in something close to a natural way is a huge technical achievement. I have nothing but respect for him and his team. It is part of a wider picture though, about data gathering, personalisation, and control of information and transactions, and it seems to me that this deserves more attention.