Parkrun is amazing; around 380,000 runners and walkers take part every Saturday morning, participating in a free timed 5K which has huge benefits for health and community.

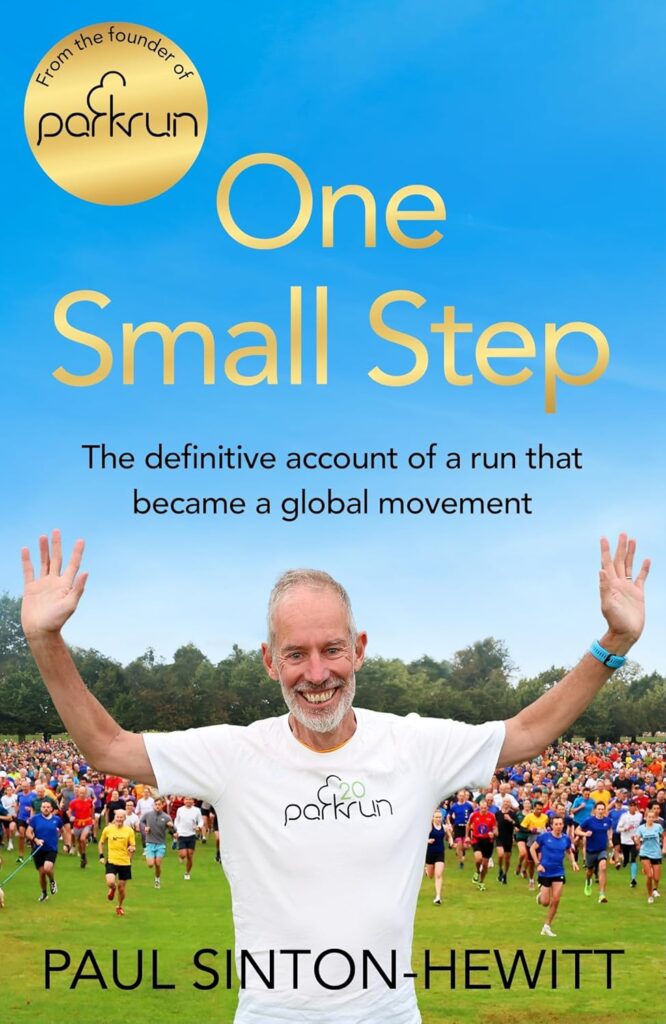

Paul Sinton-Hewitt founded the operation in London on 2nd October 2004, calling it Bushy Park Time Trial. This book is subtitled “The definitive account of a run that became a global movement,” but it really is not that. Aside from a few previews, parkrun does not start up until page 182, two -thirds of the way through.

We do get plenty of detail on the early days of parkrun, when Sinton-Hewitt bought washers and engraved them with numbers as the earliest form of what are now called finish tokens, but not that much on the years after parkrun became a big global event. The last section of the book, covering the growth of parkrun, is also the dullest.

Despite, or because, of the above, I found this book immediately gripping. Sinton-Hewitt describes his childhood in South Africa, in the days of apartheid, and the lack of affection in his family, particularly from his mother, a successful model. His mother ran off, his father had a breakdown, and for several years he was taken into care; he also describes being bullied at various institutions and it is painful to read.

Growing up he because a computer programmer and analyst, with a successful career in financial and telecommunications institutions. His knowledge of systems was put to good use when he designed parkrun; what struck me about his account of the first time trial was how similar it is to the way a parkrun is managed today.

How though did parkrun come about? In his early days Sinton-Hewitt enjoyed time trials in South Africa, and when he found himself injured and unable to run years later in the UK, he had the idea of setting up his own time trial and making it open to everyone, with the initial support coming from running clubs he knew.

There is more to it though; his troubled background and the fact that he suffered some level of breakdown of his own, for which he sought counselling, meant that he knew the value of running and community as therapy. He therefore set out to do something different than what running clubs do, welcoming anyone who showed up, with dogs if they wanted, and insisting that it should be free. He put some £50,000 of his own money into the operation until it was able to stand on its own feet with sponsorship and of course, armies of volunteers.

The book is more of an autobiography than the story of parkrun; yet it is far from a complete autobiography. In a couple of paragraphs we learn that Sinton-Hewitt met a young woman (not named), married, had two children, and separated; he does not further describe these years at all, skipping forward to his counselling following the separation.

We should conclude that Sinton-Hewitt tells his own story to the extent that he feels is necessary to explain why parkrun was formed with its particular purpose and ethos.

Although no longer running the parkrun organisation, which is now a charity, Sinton-Hewitt still has a big influence on it. There have been some challenges, particularly in 2024 when there were complaints about its policy of allowing transgender runners to participate as whatever gender they chose. Is this fair to female runners?

Sinton-Hewitt writes a couple of pages about this, and about why, in 2024, age and gender category records were removed from parkrun pages. He insists that this was not because of the transgender issue, but rather about a “focus on community, health and inclusivity.” We may never know, but it seems unlikely that the issue, and the removal of these statistics, are entirely unconnected.

It is nevertheless true that the matter of whether parkrun is a run or a race goes far beyond the transgender question. The event was set up as a time trial, and in general the purpose of a time trial is for runners trying to improve their speed. Many participants are motivated by trying to improve their times and their positions; parkrun has many of the characteristics of a race even though it claims not to be one. Sinton-Hewitt himself was a competitive athlete and shows his awareness of this ambiguity, though when pressed he states “my priority is inclusivity for all.”

While it has some race-like characteristics, parkrun is unfair in that times and positions are determined by when runners cross the finish line (known in running parlance as “gun time”), but runners cross the start line at different times, and there is often congestion so that runners cannot get up to full pace for some time, and may even be stationary while waiting for the field ahead to clear. Only the runners who start at the front of the pack get their best possible time.

This can solved with technology. Parkun could issue runners with reusable chips and use timing mats to record the start and finish time. There would be a cost, but also savings in the time and effort of recording times and processing results.

I had imagined that the reason for not using chip time was cost-based but we learn from the book that this is not so. “My view was that the use of a timing mat at parkrun would take away what I still consider to be the most precious part of the experience,” writes Sinton-Hewitt. “That moment after participants finish is a truly magical and sociable time for everyone, and frankly nothing can replace it.”

Technology will continue to advance. The chips are inexpensive; timing mats and associated equipment are more costly but will continue to get smaller and cheaper, particularly when the highest precision is not required. The use of chip timing may get harder to resist; yet one must respect Sinton-Hewitt’s commitment to preserve parkrun’s community feel.

Long may it run.

Amazon link: One Small Step by Paul Sinton-Hewitt.