If you could describe the perfect document security system, it might go something like this. “I’d like to share this document with X, Y, and Z, but I’d like control over whether they can modify it, I’d like to forbid them to share it with anyone else, and I’d like to be able to destroy their copy at a time I specify”.

This is pretty much what Microsoft’s new Azure Rights Management system promises, kind-of:

ITPros have the flexibility in their choice of storage locale for their data and Security Officers have the flexibility of maintaining policies across these various storage classes. It can be kept on premise, placed in an business cloud data store such as SharePoint, or it can placed pretty much anywhere and remain safe (e.g. thumb drive, personal consumer-grade cloud drives).

says the blog post.

There is a crucial distinction to be made though. Does Rights Management truly enforce document security, so that it cannot be bypassed without deep hacking; or is it more of an aide-memoire, helping users to do the right thing but not really enforcing it?

I tried the preview of Azure Rights Management, available here. Currently it seems more the latter, rather than any sort of deep protection, but see what you think. It is in preview, and a number of features are missing, so expect improvements.

I signed up and installed the software into my Windows 8 PC.

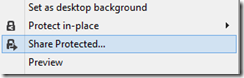

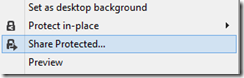

The way this works is that “enlightened” applications (currently Microsoft Office and Foxit PDF, though even they are not fully enlightened as far as I can tell) get enhancements to their user interface so you can protect documents. You can also protect *any* document by right-click in Explorer:

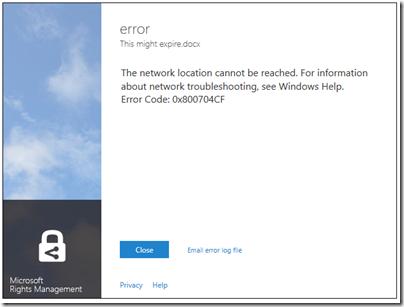

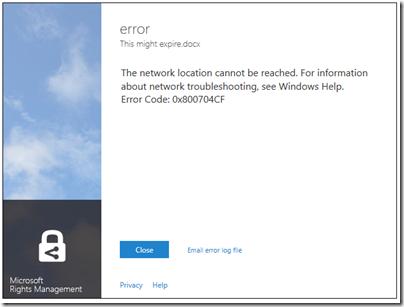

I typed a document in Word and hit Share Protected in the ribbon. Unfortunately I immediately got an error, that the network location cannot be reached:

I contacted the team about this, who asked for the log file and then gave me a quick response. The reason for the error was that Rights Management was looking for a server on my network that I sent to the skip long ago.

Many years ago I must have tried Microsoft IRM (Information Rights Management) though I barely remember. The new software was finding the old information in my Active Directory, and not trying to contact Azure at all.

This is unlikely to be a common problem, but illustrates that Microsoft is extending its existing rights management system, not creating a new one.

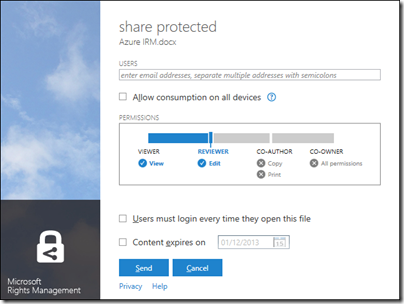

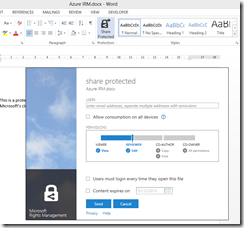

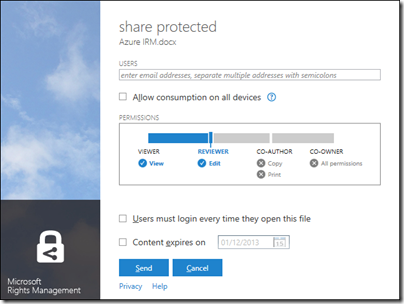

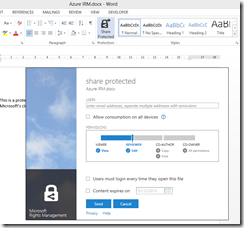

With that fixed, I was able to protect and share a document. This is the dialog:

It is not a Word dialog, but rather part of the Rights Management application that you install. You get the same dialog if you right-click any file in Explorer and choose Share Protected.

I entered a Gmail email address and sent the protected document, which was now wrapped in a file with a .pfile (Protected File) extension.

Next, I got my Gmail on another machine.

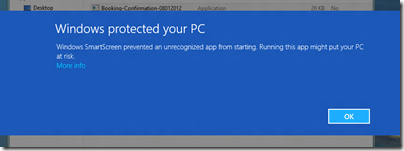

First, I tried to open the file on Android. Unfortunately only x86 Windows is supported at the moment:

There is an SDK for Android, but that is all.

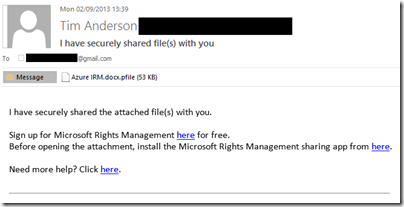

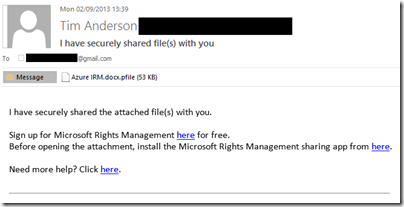

I tried again on a Windows machine. Here is the email:

There is also note in the email:

[Note: This Preview build has some limitations at this time. For example, sharing protected files with users external to your organization will result in access control without additional usage restrictions. Learn More about the Preview]

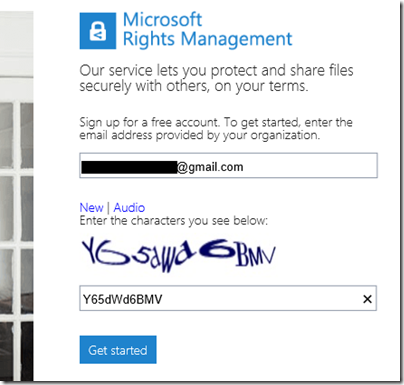

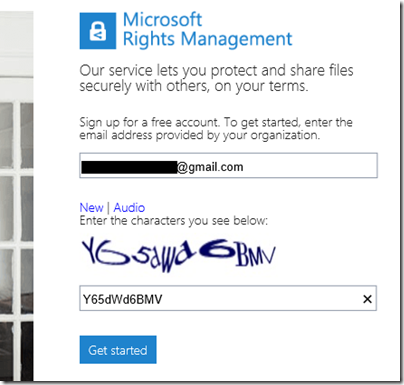

I was about to discover some more of these limitations. I attempted to sign up using the Gmail address. Registration involves solving a vile CAPTCHA

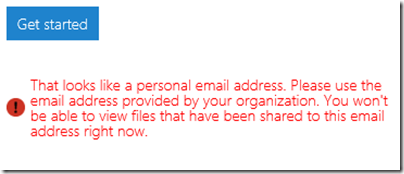

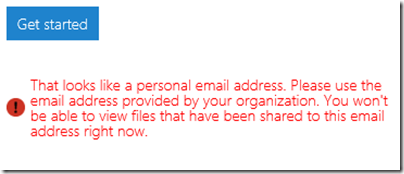

but got this message:

In other words, you cannot yet use the service with Gmail addresses. I tried it with a Hotmail address; but Microsoft is being even-handed; that did not work either.

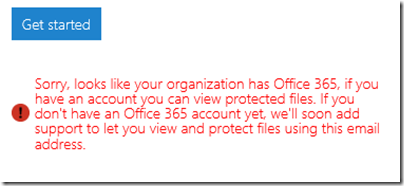

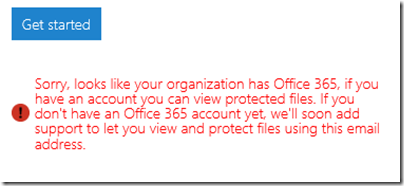

Next, I tried another email address at a different, private email domain (yes, I have lots of email addresses). No go:

The message said that the address I used was from an organisation that has Office 365 (this is correct). It then remarked, bewilderingly:

If you have an account you can view protected files. If you don’t have an Office 365 account yet, we’ll soon add support…

This email address does have an Office 365 account. I am not sure what the message means; whether it means the Office 365 account needs to sign up for rights management at £2 per user per month, or what, but it was clearly not suitable for my test.

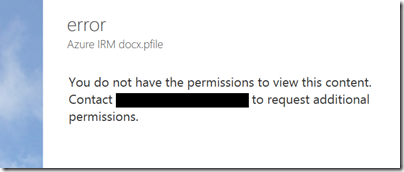

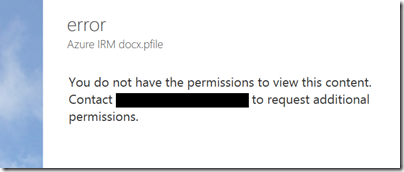

I tried yet another email address that is not in any way linked to Office 365 and I was up and running. Of course I had to resend the protected file, otherwise this message appears:

Incidentally, I think the UI for this dialog is wrong. It is not an error, it is working as designed, so it should not be titled “error”. I see little mistakes like this frequently and they do contribute to user frustration.

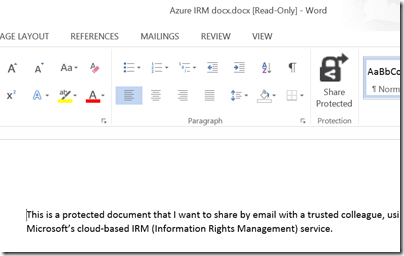

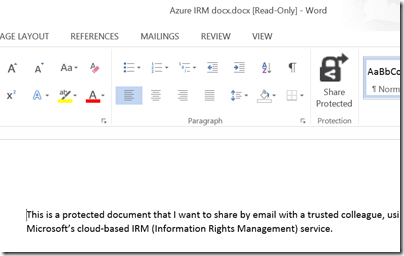

Finally, I received a document to an enabled email address and was able to open it:

For some reason, the packaging results in a document called “Azure IRM docx.docx” which is odd, but never mind.

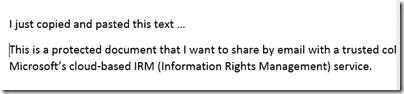

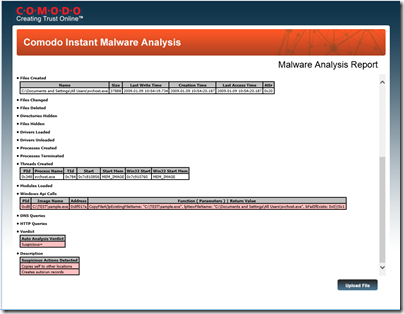

My question though: to what extent is this document protected? I took the screen grab using the Snipping Tool and pasted it into my blog for all to read, for example. The clipboard also works:

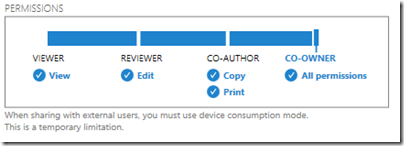

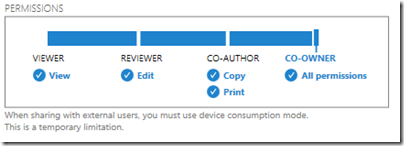

That said, the plan is for tighter protection to be offered in due course, at lease in “enlightened” applications. The problem with the preview is that if you share to someone in a different email domain, you are forced to give full access. Note the warning in the dialog:

Inherently though, the client application has to have decrypted access to the file in order to open it. All the rights management service does, really, is to decrypt the file for users logged into the Azure system and identified by their email address. What happens after that is a matter of implementation.

The consequences of documents getting into the wrong hands are a hot topic today, after Wikileaks et al. Is Microsoft’s IRM a solution?

Making this Azure-based and open to any recipient (once the limitation on “public” email addresses is lifted”) makes sense to me. However I note the following:

- As currently implemented, this provides limited security. It does encrypt the document, so an intercepted email cannot easily be read, but once opened by the recipient, anything could happen.

- The usability of the preview is horrid. Do you really want your trusted recipient to struggle with a CAPTCHA?

- Support beyond Windows is essential, and I am surprised that this even went into preview without it.

I should add that I am sceptical whether this can ever work. Would it not be easier, and just as effective (or ineffective), simply to have data on a web site with secure log-in? The idea of securely emailing documents to external recipients is great, but it seems to add immense complexity for little added value. I may be missing something here and would welcome comments.

had to sign in twice since I didn’t check “Remember password!"

If you try recursion, it will package the already packaged file.