Today Xamarin announced version 3.0 of its cross-platform mobile development tools, which let you target Android and iOS with C# and .NET. I have been trying a late beta preview.

In order to use Xamarin 3.0 with iOS support you do need a Mac. However, you can do essentially all of your development in Visual Studio, and just use the Mac for debugging.

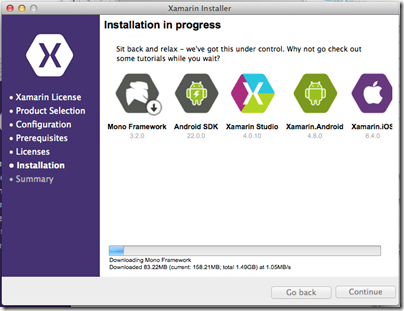

To get started, I installed Xamarin 3.0 on both Windows (with Visual Studio 2013 installed) and on a Mac Mini on the same network.

Unfortunately I was not able to sit back and relax. I got an error installing Xamarin Studio, following which the installer would not proceed further. My solution was to download the full DMG (Mac virtual disk image) for Xamarin Studio and run that separately. This worked, and I was able to complete the install with the combined installer.

When you start a Visual Studio iOS project, you are prompted to pair with a Mac. To do this, you run a utility on the Mac called Xamarin.IOS Build Host, which generates a PIN. You enter the PIN in Visual Studio and then pairing is active.

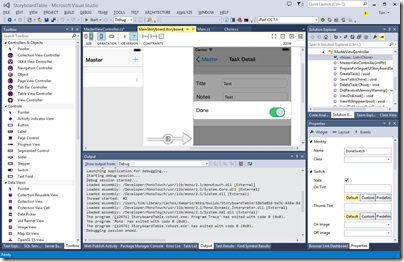

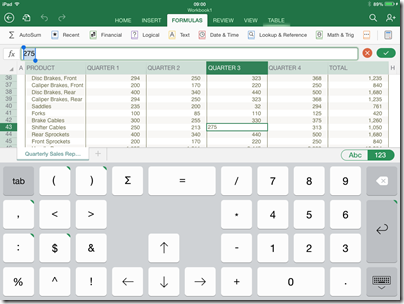

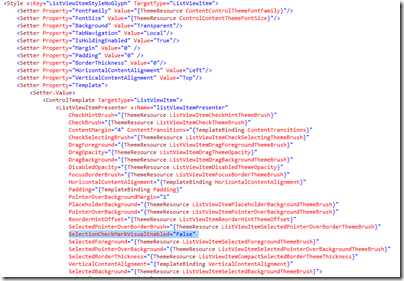

Once paired, you can create or open iOS Storyboard projects in Visual Studio, and use Xamarin’s amazing visual designer.

Please click this image to open it full-size. What you are seeing is a native iOS Storyboard file open in Visual Studio 2013 and rendering the iOS controls. On the left is a palette of visual components I can add to the Storyboard. On the right is the normal Visual Studio solution explorer and property inspector.

The way this works, according to what Xamarin CEO Nat Friedman told me, is that the controls are rendered using the iOS simulator on the Mac, and then transmitted to the Windows designer. Thus, what you see is exactly what the simulator will render at runtime. Friedman says it is better than the Xcode designer.

“The way we do event handling is far more intuitive than Xcode. It supports the new iOS 7 auto-layout feature. It allows you to live preview custom controls. Instead of getting a grey rectangle you can see it live rendered inside the canvas. We use the iOS native format for Storyboard files so you can open existing Storyboard files and edit them.”

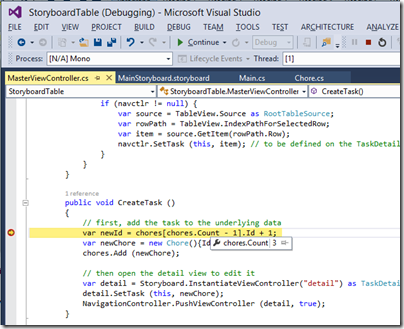

I made a trivial change to the project, configured the project to debug on the iOS simulator, and hit Start. On the Mac side, the app opened in the simulator. On the Windows side, I have breakpoint debugging.

Now, I will not pretend that everything ran smoothly in the short time I have had the preview. I have had problems with the pairing after switching projects in Visual Studio. I also had to quit and restart the iOS Simulator in order to get rendering working again. This is an amazing experience though, combining remote debugging with a visual designer on Visual Studio in Windows that remote-renders design-time controls.

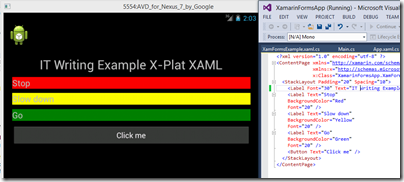

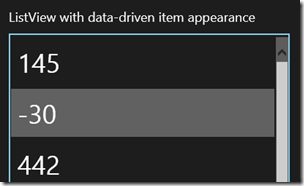

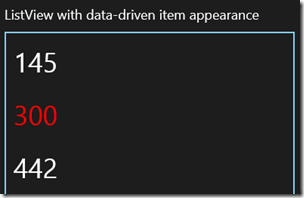

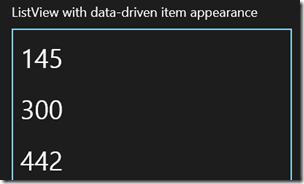

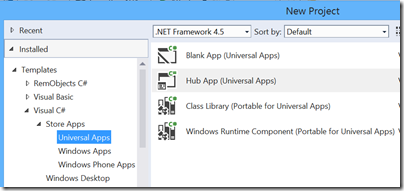

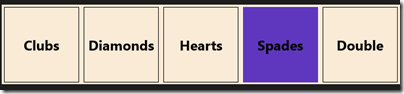

Still, time to look at another key new feature in Xamarin 3: Xamarin Forms. This is none other than our old friend XAML, implemented for iOS and Android. The Mono team has some experience implementing XAML on Linux, thanks to the Moonlight project which did Silverlight on Linux, but this is rather different. Xamarin forms does not do any custom drawing, but wraps native controls. In other words, it like is the Eclipse SWT approach for Java, and not like the Swing approach which does its own drawing. This is keeping with Xamarin’s philosophy of keeping apps as native as possible, even though the very existence of a cross-platform GUI framework is something of a compromise.

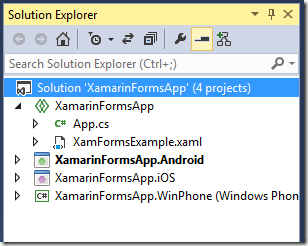

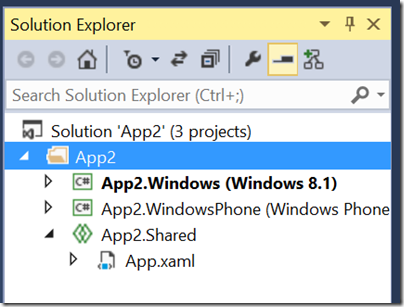

I have not had long to play with this. I did create a new Xamarin Forms project, and copy a few lines of XAML from a sample into a shared XAML file. Note that Xamarin Forms uses Shared Projects in Visual Studio, the same approach used by Microsoft’s Universal Apps. However, Xamarin Forms apps are NOT Universal Apps, since they do not support Windows 8 (yet).

In a Shared Project, you have some code that is shared, and other code that is target-specific. By default hardly any code is shared, but you can move code to the shared node, or create new items there. I created XamFormsExample.xaml in the shared node, and amended App.cs so that it loads automatically. Then I ran the project in the Android emulator.

I was also able to run this on iOS using the remote connection.

I noticed a few things about the XAML. The namespace is:

xmlns="http://xamarin.com/schemas/2014/forms"

xmlns:x="http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2009/xaml"

I have not seen this before. Microsoft’s XAML always seems to have a “2006” namespace. For example, this is for a Universal App:

xmlns="http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2006/xaml/presentation"

xmlns:x=http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2006/xaml

However, XAML 2009 does exist and apparently can be used in limited circumstances:

In WPF, you can use XAML 2009 features, but only for XAML that is not WPF markup-compiled. Markup-compiled XAML and the BAML form of XAML do not currently support the XAML 2009 language keywords and features.

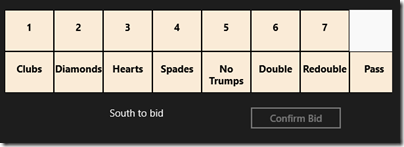

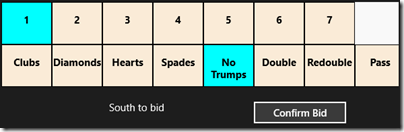

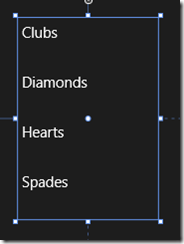

It’s odd, because of course Xamarin’s XAML is cut-down compared to Microsoft’s XAML. That said, I am not sure of the exact specification of XAML in Xamarin Forms. I have a draft reference but it is incomplete. I am not sure that styles are supported, which would be a major omission. However you do get layout managers including AbsoluteLayout, Grid, RelativeLayout and StackLayout. You also get controls (called Views) including Button, DatePicker, Editor, Entry (single line editor), Image, Label, ListView, OpenGLView, ProgressBar, SearchBar, Slider, TableView and WebView.

Xamarin is not making any claims for compatibility in its XAML implementation. There is no visual designer, and you cannot port from existing XAML code. The commitment to wrapping native controls may limit prospects for compatibility. However, Friedman did say that Xamarin hopes to support Universal Apps, ie. to run on Windows 8 as well as Windows Phone, iOS and Android. He said:

I think it is the right strategy, and if it does take off, which I think it will, we will support it.

Friedman says the partnership with Microsoft (which begin in November 2013) is now close, and it would be reasonable to assume that greater compatibility with Microsoft XAML is a future goal. Note that Xamarin 3 also supports Portable Class Libraries, so on the non-visual side sharing code with Microsoft projects should be straightforward.

Personally I think both the Xamarin forms and the iOS visual designer (which, note, does NOT support Xamarin Forms) are significant features. The iOS designer matters because you can now do almost all of your cross-platform mobile development within Visual Studio, even if you want to follow the old Xamarin model of a different, native user interface for each platform; and Xamarin Forms because it enables a new level of code sharing for Xamarin projects, as well as making XAML into a GUI language that you can use across all the most popular platforms. Note that I do have reservations about XAML; but it does tick the boxes for scaling to multiple form factors and for enormous flexibility.