2011 felt like a pivotal year in technology. What was pivoting? Well, users are pivoting away from networks and PCs and towards cloud and devices. The obvious loser is Microsoft, which owns PCs and networks but is a distant follower in devices and has mixed prospects in the cloud. Winners include Apple, Google, Amazon, and Android vendors. These trends have been obvious for some time, but in 2011 we saw dramatic evidence of their outcome. As 2011 draws to a close, here is my take on ten happenings, presented as the first ever ITWriting.com annual awards.

1. Most dramatic moment award: Nokia’s burning platform and alliance with Microsoft

In February Nokia’s Stephen Elop announced an alliance with Microsoft and commitment to Windows Phone 7. In October we saw the first results in terms of product: the launch of the Lumia smartphone. It is a lovely phone though with some launch imperfections like too short battery life. We also saw greatly improved marketing, following the dismal original Windows Phone 7 launch a year earlier. Enough? Early indications are not too good. Simply put, most users want iOS or Android, and the app ecosystem, which Elop stated as a primary reason for adoption Windows Phone, is not there yet. Both companies will need to make some smart moves in 2012 to fix these issues, if it is possible. But how much time does Nokia have?

2. Riskiest technology bet: Microsoft unveils Windows 8

In September 2011 Microsoft showed a preview of Windows 8 to developers at its BUILD conference in California. It represents a change of direction for the company, driven by competition from Apple and Android. On the plus side, the new runtime in Windows 8 is superb and this may prove to be the best mobile platform from a developer and technical perspective, though whether it can succeed in the market as a late entrant alongside iOS and Android is an open question. On the minus side, Windows 8 will not drive upgrades in the same way as Windows 7, since the company has chosen to invest mainly in creating a new platform. I expect much debate about the wisdom of this in 2012.

Incidentally, amidst all the debate about Windows 8 and Microsoft generally, it is worth noting that the other Windows 8, the server product, looks like being Microsoft’s best release for years.

3. Best cloud launch: Office 365

June 2011 saw the launch of Office 365, Microsoft’s hosted collaboration platform based on Exchange and SharePoint. It was not altogether new, since it is essentially an upgrade of the older BPOS suite. Microsoft is more obviously committed to this approach now though, and has built a product that has both the features and the price to appeal to a wide range of businesses, who want to move to the cloud but prefer the familiarity of Office and Exchange to the browser-based world of Google Apps. Bad news though for Microsoft partners who make lots of money nursing Small Business Server and the like.

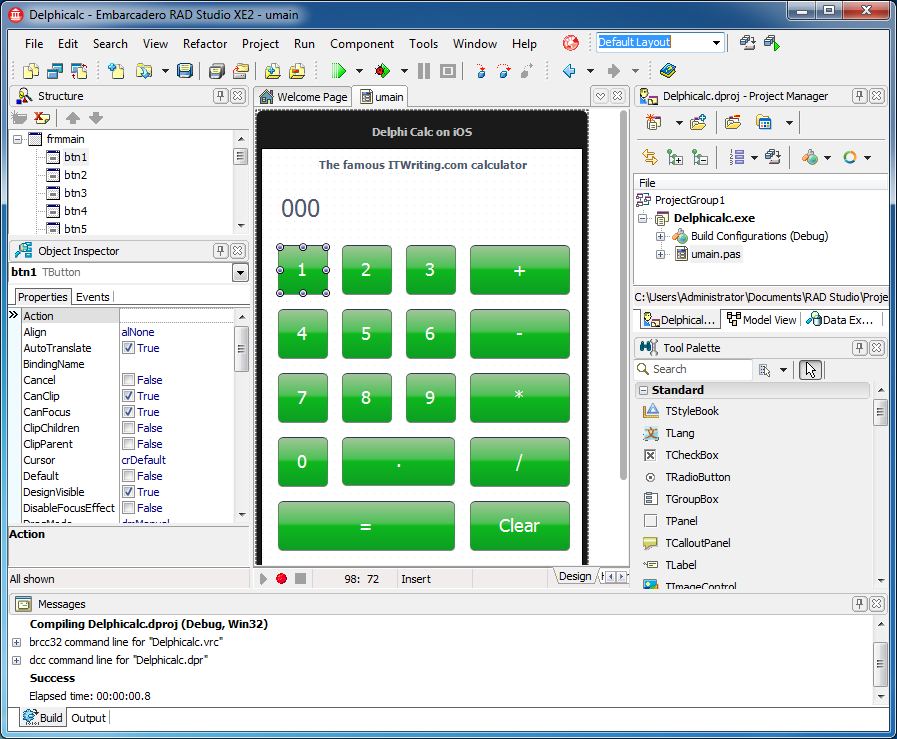

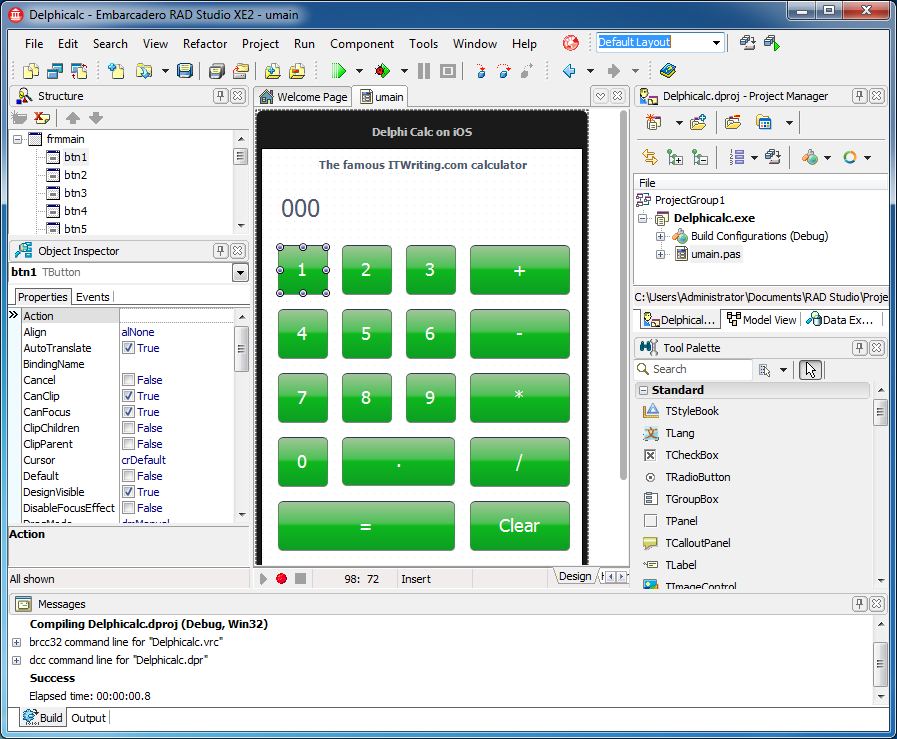

4. Most interesting new cross-platform tool: Embarcadero Delphi for Windows, Mac and iOS

Developers, at least those who have still heard of Embarcadero’s rapid application development tool, were amazed by the new Delphi XE2 which lets you develop for Mac and Apple iOS as well as for Windows. This good news was tempered by the discovery that the tool was seemingly patched together in a bit of a hurry, and that most existing application would need extensive rewriting. Nevertheless, an interesting new entrant in the world of cross-platform mobile tools.

5. Biggest tech surprise: Adobe shifts away from its Flash Platform

This one caught me by surprise. In November Adobe announced a shift in its business model away from Flash and away from enterprise development, in favour of HTML5, digital media and digital marketing. It also stated that Flash for mobile would no longer be developed once existing commitments were completed. The shift is not driven by poor financial results, but rather reflects the company’s belief that this will prove a better direction in the new world of cloud and device. Too soon and too sudden? Maybe 2012 will show the impact.

6. Intriguing new battle award: NVIDIA versus Intel as GPU computing catches on

In 2011 NVIDIA announced a number of wins in the supercomputing world as many of these huge machines adopted GPU Computing, and I picked up something of a war of words with Intel over the merits of what NVIDIA calls heterogeneous computing. Intel is right to be worried, in that NVIDIA is seeing a future based on its GPUs combined with ARM CPUs. NVIDIA should worry too though, not only as Intel readies its “Knight’s Corner” MIC (Many Integrated Core) chips, but also as ARM advances its own Mali GPU; there is also strong competition in mobile GPUs from Imagination, used by Apple and others. The GPU wars will be interesting to watch in 2012.

7. Things that got worse award: Spotify. Runners up: Twitter, Google search

Sometimes internet services come along that are so good within their niche that they can only get worse. Spotify is an example, a music player that for a while let you play almost anything almost instantly with its simple, intuitive player. It is still pretty good, but Spotify got worse in 2011, with limited plays on free account, more intrusive ads, and sign-up now requires a Facebook login. Twitter is another example, with URLS now transformed to t.co shortcuts whether you like it not and annoying promoted posts and recommended follows. Both services are desperately trying to build a viable business model on their popularity, so I have some sympathy. I have less sympathy for Google. I am not sure when it started making all its search results into Google links that record your click before redirecting you, but it is both annoying and slow, and I am having another go with Bing as a result.

8. Biggest threat to innovation: Crazy litigation from Lodsys, Microsoft, Apple

There has always been plenty of litigation in the IT world. Apple vs Microsoft regarding graphical user interfaces 1994; Sun vs Microsoft regarding Java in 1997; SCO vs IBM regarding UNIX in 2003; and countless others. However many of us thought that the biggest companies exercised restraint on the grounds that all have significant patent banks and trench warfare over patent breaches helps nobody but lawyers. But what if patent litigation is your business model? The name Lodsys sends a chill though any developer’s spine, since if you have an app that supports in-app purchases you may receive a letter from them, and your best option may be to settle though others disagree. Along with Lodsys and the like, 2011 also brought Microsoft vs several OEMs over Android, Apple vs Samsung over Android, and much more.

9. Most horrible year award: HP

If any company had an Annus Horribilis it was HP. It invested big in WebOS, acquired with Palm; launched the TouchPad in July 2011; announced in August that it was ceasing WebOS development and considering selling off its Personal Systems Group; and fired its CEO Leo Apotheker in September 2011.

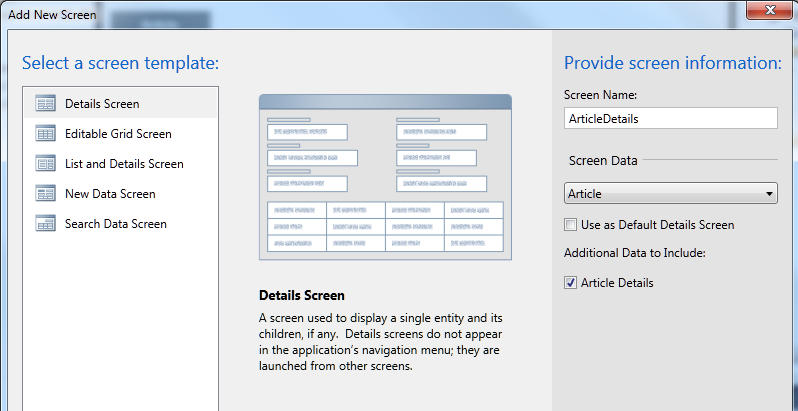

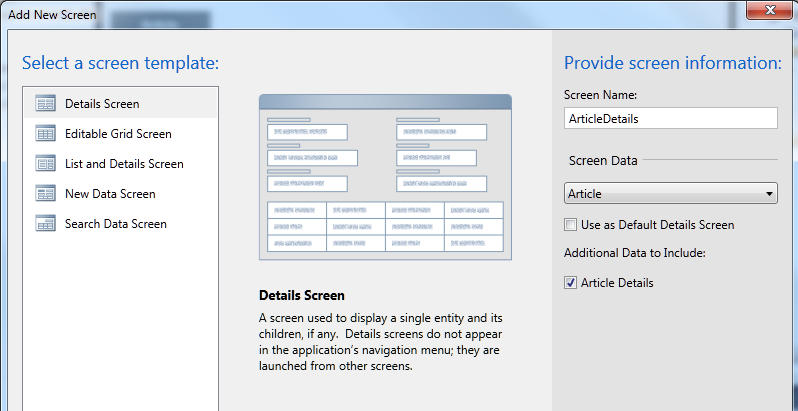

10. Product that deserves better award: Microsoft LightSwitch

On reflection maybe this award should go to Silverlight; but it is all part of the same story. Visual Studio LightSwitch, released in July 2011, is a model-driven development tool that generates Silverlight applications. It is nearly brilliant, and does a great job of making it relatively easy to construct business database applications, locally or on Windows Azure, complete with cross-platform Mac and Windows clients, and without having to write much code. Several things are unfortunate though. First, usual version 1.0 problems like poor documentation and odd limitations. Second, it is Silverlight, when Microsoft has made it clear that its future focus is HTML 5. Third, it is Windows and (with limitations) Mac, at a time when something which addresses the growing interest in mobile devices would be a great deal more interesting. Typical Microsoft own-goal: Windows Phone 7 runs Silverlight, LightSwitch generates Silverlight, but no, your app will not run on Windows Phone 7. Last year I observed that Microsoft’s track-record on modelling in Visual Studio is to embrace in one release and extinguish in the next. History repeats?