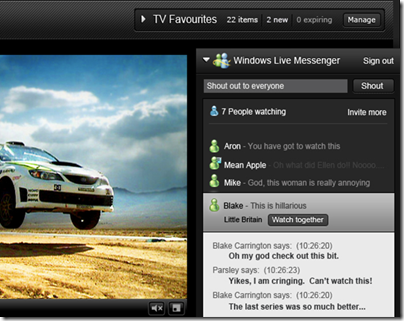

The BBC released a new sports app last week. In the comments to the announcement though, there is little attention given to the app or its content. Rather, the discussion is about why the BBC has apparently prioritised iOS over Android, since the Android version is not yet ready, with an occasional interjection from a Windows Phone user about why there is nothing at all for them.

BBC I think you need to actually catch up on what’s happening. Android is huge now. You should be launching both platforms together. A lot of people I know have switched to an Android device and your app release almost feels like discrimination!

says one user; while the BBC’s Lucie Mclean, product manager for mobile services, replies:

Back in July, when we launched the Olympics app for iPhone and Android together, we saw over three times as many downloads of the iPhone version. Android continues to grow apace but this, together with the development and testing complexity, led us to the decision to phase the iOS app first.

BBC Technology correspondent spoke to head of iPlayer David Danker about this problem back in December. Danker claims that the BBC spends more “energy” (I am not sure if that means time or just frustration) on Android than Apple, and mainly blames Android fragmentation and the existence of more low-end devices for the delays:

It’s not just fragmentation of the operating system – it is the sheer variety of devices. Before Ice Cream Sandwich (an early variant of the Android operating system) most Android devices lacked the ability to play high quality video. If you used the same technology as we’ve always used for iPhone, you’d get stuttering or poor image quality. So we’re having to develop a variety of approaches for Android

A couple of things are obvious. One is that Apple’s clearly-defined iOS development platform and limited range of devices is a win for developers. Despite frustrations over things like the way apps are sandboxed or Apple’s approval process, it is easier to target iOS than Android because the platform is more consistent. iOS users are also relatively prosperous and highly engaged with the web and the app store, so that even though Apple’s overall platform market share has fallen behind that of Android, it is still the most important market in some contexts.

Another is that the BBC cannot win. From a PR perspective, it should probably do simultaneous iOS and Android releases even if that means a delay, but even then there will be complaints over differences in detail between iOS and Android implementations. Further, the voices of those neglected minorities, such as Windows Phone and soon, Blackberry 10 users, will grow louder if iOS and Android achieve parity.

In all this, it is worth noting that the BBC gets one thing right, prioritising the mobile web:

The decision to launch the core mobile browser site first (before either app) was itself to ensure that users got a quality product across as wide a range of devices as possible.

says Mclean.

Personally I wonder if the the BBC needs to do all these niche apps. The iPlayer app is the one that really matters, particularly when it offers download for offline viewing, but is a sports app so necessary?

Should it not concentrate instead on first, the mobile web site, and second, APIs that third-party developers can use, enabling developers on each platform to create high quality apps?

Another option would be to make cross-platform a religion, and cover all significant platforms while giving up some of the benefits of native code. High quality video is a problem; but in many scenarios the quality of the video is not such a big issue provided that it works and is intelligible.

Perhaps the BBC could make Cordova (an open source framework for cross-platform mobile apps) video work better. Having the BBC invest its publicly funded resources into open source cross-platform development is better PR than developing expensive apps for single platforms.