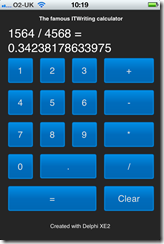

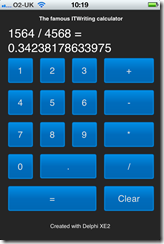

I am sure all readers of this blog will know by now that Delphi XE2 (and RAD Studio XE2) has been released, and that to the astonishment of Delphi-watchers it supports not only 64-bit compilation on Windows, but also cross-platform apps for Windows, Mac OS X and even iOS for iPhone and iPad (with Android promised).

I tried this early on and was broadly impressed – my app worked and ran on all three platforms.

However it is an exceedingly simple app, pretty much Hello World, and there are some worrying aspects to this Delphi release. FireMonkey is based on technology from KSDev, which was acquired by Embarcadero in January this year. To go from acquisition to full Delphi integration and release in a few months is extraordinary, and makes you wonder what corners were cut.

It seems that corners were cut: you only have to read this post by developer and Delphi enthusiast Chris Rolliston:

To put it bluntly, FireMonkey in its current state isn’t good enough even for writing a Notepad clone (I know, because I’ve been trying). You can check out Herbert Sauro’s blog for various details (here, also a follow up post here). For my part, here’s a highish-level list of missing features and dubious coding practices, written from the POV of FireMonkey being a VCL substitute on the Mac (since on OS X, that is what it is).

Fortunately I did not write a Notepad clone, I wrote a Calculator clone, which explains why I did not run into as many problems.

Update: See also A look at the 3D side of FireMonkey by Eric Grange:

…if you want to achieve anything beyond a few poorly texture objects, you’ll need to design and write a lot of custom code rather than rely on the framework… with obvious implications of obsolescence and compatibility issues whenever FMX finally gets the features in standard.

There has already been an update for Delphi XE2 which is said to fix over 120 bugs as well as an open source licensing issue. I also noticed better performance for my simple iOS calculator after the update.

Still, FireMonkey early adopters face some significant issues if they are trying to make VCL-like applications, which I am guessing is a common scenario. There is a mismatch here, in that FireMonkey is based on VGScene and DXScene from KSDev, and the focus of those libraries was rich 2D and 3D graphics. Some Delphi developers undoubtedly develop rich graphical applications, but a great many do not, and I would judge that if Embarcadero had been able to deliver something more like a cross-platform VCL that just worked, the average Delphi developer would have been happier.

The company must be aware of this, and one reading of the journey from VSCene/DXScene to FireMonkey is that Embarcadero has been madly stuffing bits of VCL into the framework. Eventually, once the bugs are shaken out and missing features implemented, we may have something close to the ideal.

In the meantime, you can make a good case for Adobe Flash and Flex if what you really want is cross-platform 2D and 3D graphics; while VCL-style developers may be best off using the current FireMonkey more for trying out ideas and learning the new Framework than for real work, pending further improvements.

On the positive side, even though FireMonkey is a bit rough, Embarcadero has delivered a development environment for Windows and Mac that works. You can work in the familiar Delphi IDE and code around any problems. The Delphi community is not short of able developers who will share their workarounds.

I have some other questions about Delphi. Why are there so many editions, and who uses the middleware framework DataSnap, or other enterprisey features like UML modeling?

There appear to be five editions of Delphi XE2: Starter, Professional, Enterprise, Ultimate and Architect, where Architect has features missing in Ultimate – should the Ultimate be called the Penultimate? It breaks down like this:

- Starter: low cost, restrictive license that is mainly non-commercial (you are allowed revenue up to $1000 per year). No 64-bit, no Mac or iOS. $199.00

- Professional: The basic Delphi product. Missing a few features like UML diagramming, no DataSnap. Limited IntraWeb. $899.00.

- Enterprise: For more than double the price, you get DataSnap and dbExpress server drivers. $1,999.00

- Ultimate: Adds a developer edition of Embarcadero’s DBPowerStudio. $2999.00

- Architect: Adds more UML modeling, and a developer edition of Embarcadero’s ER/Studio database modeling tool. $3499.00

The RAD Studio range is similar, but adds C++ Builder, PHP and .NET development. No Starter version. Prices from $1399.00 for Professional to $4299.00 for Architect. The non-Ultimate Ultimate is $3799.00.

All prices discounted by around 40% for upgraders.

The problem for Embarcadero is that Delphi is such a great and flexible tool that you can easily use it for database or multi-tier applications with just the Professional edition. See here, for example, for REST client and server suggestions. Third parties like devart do a good job of providing alternative data access components and dbExpress drivers. I would be interested to know, therefore, what proportion of Delphi developers buy into the official middleware options.

As an aside, I wondered about DataSnap licensing. I looked at the DataSnap page which says for licensing information look here – which is a MIDAS article from 2000, yes Embarcadero, that is 11 years ago. Which proves if nothing else what a ramshackle web site has evolved over the years.

Personally I would prefer to see Embarcadero focus on the Professional edition and improve humdrum things like FireMonkey documentation and bugs, and go easy on enterprise middleware which is a market that is well served elsewhere.

I have seen huge interest in Delphi as a productive, flexible, high-performance tool for Windows, Mac and mobile, but the momentum is endangered by quality issues.