It was March 2009 when I took part in an unusual Hi-Fi show, variously known as the Scalford, Wigwam, Wam or Pie Show (Pie show because Scalford is near Melton Mowbray, home of the Pork Pie, and Pie rhymes with Hi-Fi). Wigwam was and is a Hi-Fi enthusiasts forum and the idea was to put on a show where the kit on show was not the latest stuff from big brands, but rather actual systems in use by enthusiasts. Without the normal income from commercial exhibitors, the cost of the hotel booking was met by the entrance fee (£10 as I recall). Exhibitor rooms were free other than a small contribution to public liability insurance. The early shows were run by audio show specialists Chester who did it, they said, as a community building exercise.

Scalford Hall is an English country hotel which must once have been a grand country residence. it is beautiful, rambling and impractical, but full of atmosphere.

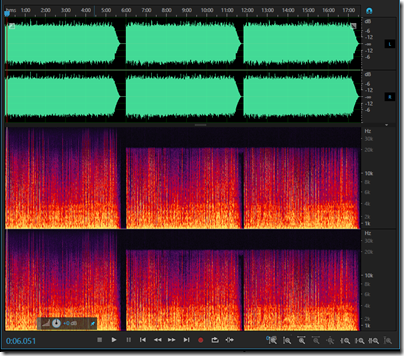

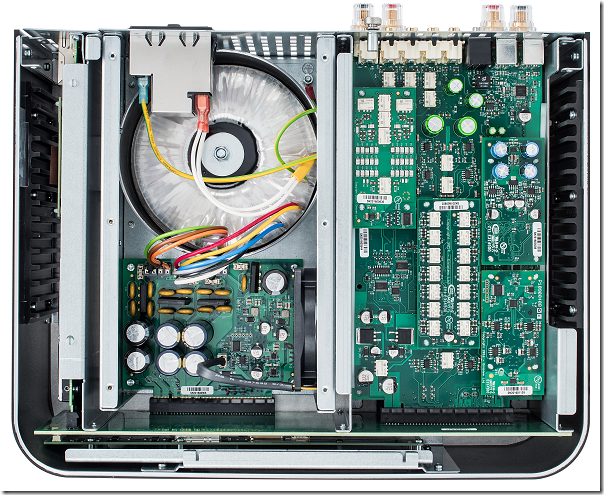

The show was an extraordinary success. There was a vastly greater variety of gear on show than at commercial shows, ranging from conventional and modern to old and home-made. The exhibitors were enthusiasts who loved to talk about their systems, and the sound achieved was in general rather better than most. A few pictures, not from the first show:

Personally I had a great time at Scalford and exhibited 8 years in succession (starting with the first). Hmm let me see:

2009: plain Squeezebox, Naim 32.5/Hicap/250 and Kans

2010: Ergo speakers designed by James at another HiFi forum, Pink Fish Media, loaned to me for the event. Same source and amplification.

2011: Active Speakers AVI ADM 9 with BK subwoofer

2012: Linn Kaber loudspeakers with Naim amplification; my least successful room I feel. I thought the Naim amplifier would get the Kabers sounding at their best but the sound was average and I was not sure how to fix it.

2013: Active Speakers Behringer B3031A. The theme here was how to get a great sound on a small budget, and the Behringer active speakers offer a lot for the price.

2014: Amplifier comparison Naim as above vs Yamaha AS500

This was fascinating; a modern budget amplifier compared to a classic pre-power combination loved by many but also considered coloured. Most thought both sounded great and were not sure which was which.

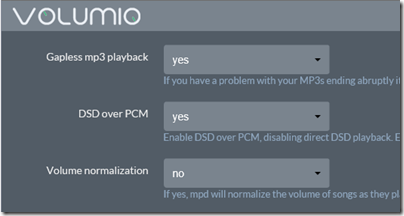

2015: DSD vs PCM comparison using Teac DSD DAC

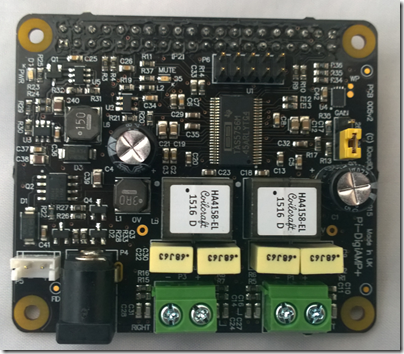

2016: Raspberry Pi system no separate amplifier

Some of these events have separate write-ups on this blog.

My goal was not to have the best sounding system but to do something interesting and enjoyable.

Enjoyable it was, but also hard work – at first I didn’t bother booking a room for the night as I lived within 45 minute drive, but I gradually realised that staying over worked better both for access to the room and for hearing other rooms the night before.

Heaving equipment around is no fun even though I didn’t have the heaviest stuff, even so amplifiers, subs and speaker stands are hefty enough. Some of my stuff got a bit bashed about too, though scratches rather than real damage.

The earliest events were run supposedly at break-even or thereabouts by Chester. The only commercial presence in the early shows was a record shop in the lobby.

I was personally fine with everything as we were doing something a bit different that would not otherwise be possible.

Gradually more commercial rooms appeared and it became harder and harder to secure good rooms. My room in year 1 was brilliant and sounded great as a result. Many of the rooms though were small hotel bedrooms in an extension rather than the older part of the building, with poor sound insulation. It was hard to get a good sound in these rooms.

I also began (speaking personally) to feel a bit unappreciated as it was the exhibitors who made the event worth going to, but we paid for the privilege and if someone managed to make some money (as I believe the organisers did in some years) none of it came to us not even a free beer or two. After the first couple of shows the organisation passed to the owners of the WigWam forum, which itself changed hands a few times. In 2017 my heart was no longer in it and I did not exhibit.

The trend towards greater commercialism continues and the WigWam’s current owners now promote the event as "Europe’s Biggest HiFi Enthusiasts Show". The cost for exhibitors has increased and now starts at £85. I have fond recollections of the show and hope it goes from strength to strength, but last year felt it was no longer for me.

Scalford was a wonderful venue, quirky and romantic, visitors could still be surprised to open a door or ascend a stairway and find a corridor of rooms they had somehow missed. Of course it was also a bit impractical and the catering rather ho-hum but it wasn’t a big deal for me.

The show is now moving to Kegworth, just off the M1 near Nottingham. The move to a hotel handy for the motorway and airport is another step away from the atmosphere and culture of the initial concept.

That said, I have no doubt that it will remain a remarkable and unusual event and hope it continues to be a great success.