Google App Engine will be leaving preview status and becoming more expensive in the second half of September, according to an email sent to App Engine administrators:

We are updating our policies, pricing and support model to reflect its status as a fully supported Google product … almost all applications will be billed more under the new pricing.

Along with the new prices there are improvements in the support and SLA (Service Level Agreement) for paid applications. For example, Google’s High Replication Datastore will have a new 99.95% uptime SLA (Service Level Agreement).

Premier Accounts offer companies “as many applications as they need” for $500 per month plus usage fees. Otherwise it is $9.00 per app.

Free apps are now limited to a single instance and 1GB outgoing and incoming bandwidth per day, 50,000 datastore operations, and various other restrictions. The “Instance” pricing is a new model since previously paid apps were billed on the basis of CPU time per hour. Google says in the FAQ that this change removes a barrier to scaling:

Under the current model, apps that have high latency (or in other words, apps that stay resident for long periods of time without doing anything) can’t scale because doing so is cost-prohibitive to Google. This change allows developers to run any sort of application they like but pay for all of the resources that your applications use.

Having said that, the free quota remains generous and sufficient to run a useful application without charge. Google says:

We expect the majority of current active apps will still fall under the free quotas.

Free apps are limited to a single instance, 1GB outgoing and 1GB incoming bandwidth per day, and 50,000 datastore operations, among other restrictions.

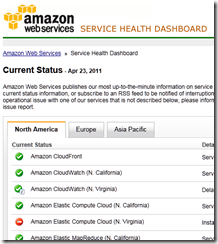

The pricing is complex, and comparing prices between cloud providers such as Amazon, Microsoft and Salesforce.com is even more complex as each one has its own way of charging. My guess is that Google will aim to be at least competitive with AWS (Amazon Web Services), while Microsoft Azure and Salesforce.com seem to be more expensive in most cases.