I have an online bridge game in development (yes, still!) and it is written in ASP.NET Core with C#. One of the things that interests bridge players is called double-dummy analysis; this is where you look at what would be the best play in a game if you knew where all the cards were, whereas when actually playing bridge you only see your own cards and, during play, another hand called Dummy, so half the cards are hidden.

Double-dummy analysis is a solved problem and bridge programmers benefit from an open source library called DDS (Double Dummy Solver) written primarily by Bo Hagland and Soren Hein. This is a C++ DLL that can also be compiled for Linux and MacOS.

I wanted to integrate DDS into the bridge game in order to give players information at the end of a game including whether they were in the optimum contract and whether they beat the optimum score. I started by doing a new C# wrapper for DDS though borrowing from the work here. My version is 64-bit and wraps a few more functions. I compiled the native DLL for Windows and Linux using OpenMP for concurrency, which considerably improves performance (Boost is another option but I did not find much difference).

Note: the usual caveats about P/Invoke apply here. During one of my tests I actually crashed the container running the app. The ASP.NET developers do a lot of work to make the platform reliable, and doing P/Invoke may introduce instability.

I added my wrapper into the ASP.NET application and it worked fine on my development machine. I deployed it to App Service and the P/Invoke calls did not work. Fixing this required a bit of a deep dive into Azure App Service for Linux.

I am deploying the native code .so library into the same directory as the compiled .NET code for the rest of the application. The error I got was:

Cannot open shared object file: No such file or directory

I raised the topic on Stack Overflow.

One of the things that puzzled me was that the unit tests, which include the P/Invoke code, ran OK in Azure Pipelines, which I use for deployment. But not when deployed.

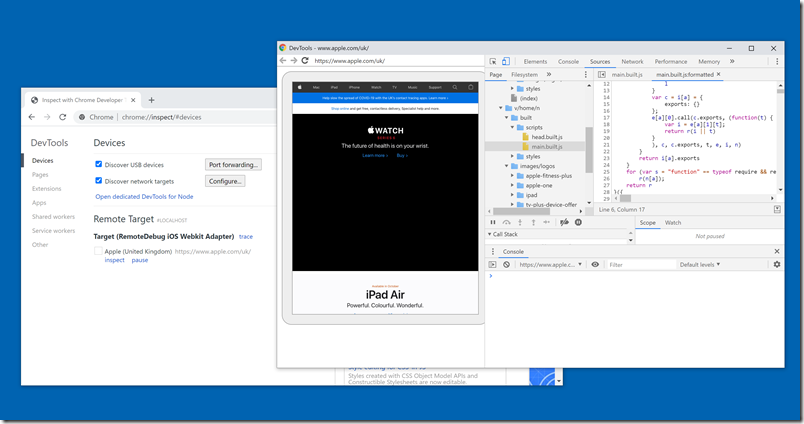

The first point is that you get the “No such file” error not only when the file itself is not present (it was) but also when a dependency is missing. So step one is to SSH into the container running the ASP.NET app, which you can do with the Development Tools in the Azure portal. Note that with Azure App Service for Linux the app always runs in a container.

This gives you root permissions in the container though not to the host operating system. Navigate to the directory with the troublesome library and type:

ldd libdds.so

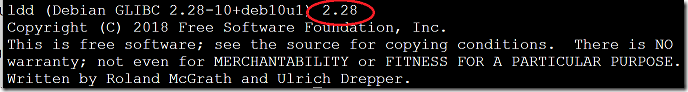

(or the name of your library). This will tell you if any dependencies are missing or other issues. I noticed two things. One is that it was missing the dependency libgomp.so.1 which is the OpenMP library. Second, ldd reported that my library required at least GLIBC 2.29 where the available version was 2.28.

How could I fix the GLIBC version? This is determined by the version of Linux and you can use

ldd – version

to check the version you have. In my case it said I had Debian with GLIBC 2.28:

I did some more research. If you really want to know about Azure App Service for Linux, there are a few key documents.

The basics here: Operating system functionality – Azure App Service | Microsoft Learn

The FAQ here: App Service on Linux FAQ | Microsoft Learn

Here you will learn details like why you cannot use a file-based database like SQLite in Azure App Service for Linux:

“The file system of your application is a mounted network share. This enables scale out scenarios where your code needs to be executed across multiple hosts. Unfortunately this blocks the use of file-based database providers like SQLite since it’s not possible to acquire exclusive locks on the database file.”

But I digress. To go deeper still, check this post by Jim Cheshire:

Things You Should Know: Web Apps and Linux – Microsoft Tech Community

which has lots of critical information, like why a custom container on App Service must respond to ping.

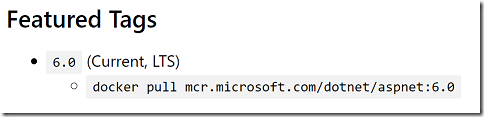

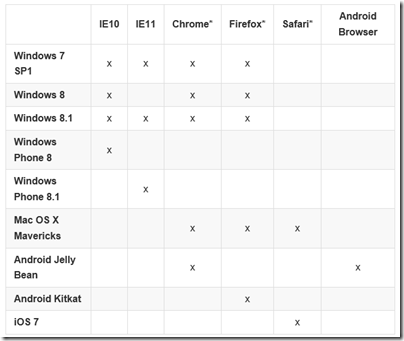

So after reading through all this and greatly improving my understanding of how App Service for Linux works, I got to the heart of my problem. When you deploy a .NET Core application to App Service for Linux, it will by default use a container from the Microsoft Artifact Registry that matches the version of .NET you are using. If you check this page you will see that the current version for ASP.NET Core 6.0 is tagged mcr.microsoft.com/dotnet/aspnet:6.0

If you examine this container you will find that it runs Debian Buster which uses GLIBC 2.28. It is a matter of slight concern since Debian Buster is shown on the Debian releases wiki as having an approximate end of life August 2022, though the LTS project extends that to June 2024.

Still, now I knew how to fix my problem. Either use a custom container image, or upgrade to .NET 7, or recompile libdds.so to run on Debian Buster.

I decided that the easiest short-term solution was to recompile. I downloaded Buster and recompiled the library.

What about libgomp.so.1? This was kind-of fixable by using SSH to run:

apt-get update

apt-get install libgomp1

This is not great though since Azure could replace the container at any time, and always if you do something like scale the plan up or down, to change the specification of the VM. I tried copying the buster version of libgomp.so.1 to the application directory. It works, but I also needed to add a linker option to enable DDS to use a library in the same directory:

-Wl,-rpath='${ORIGIN}'

as explained here.

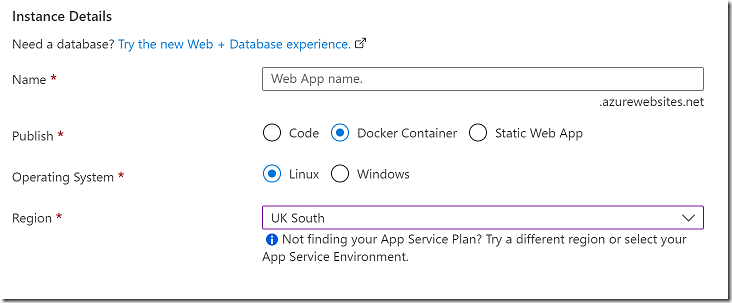

I think a better solution is to move to deploying a custom container to App Service, which is an option:

Care is needed though as there is a bit of special sauce in the official container images if you want features like SSH in the portal to work properly. It also means revisiting my deployment scripts, so the above hack was an easier and quicker workaround for me.